🤔 Frequently Asked Questions

Why can I change my votes only once?

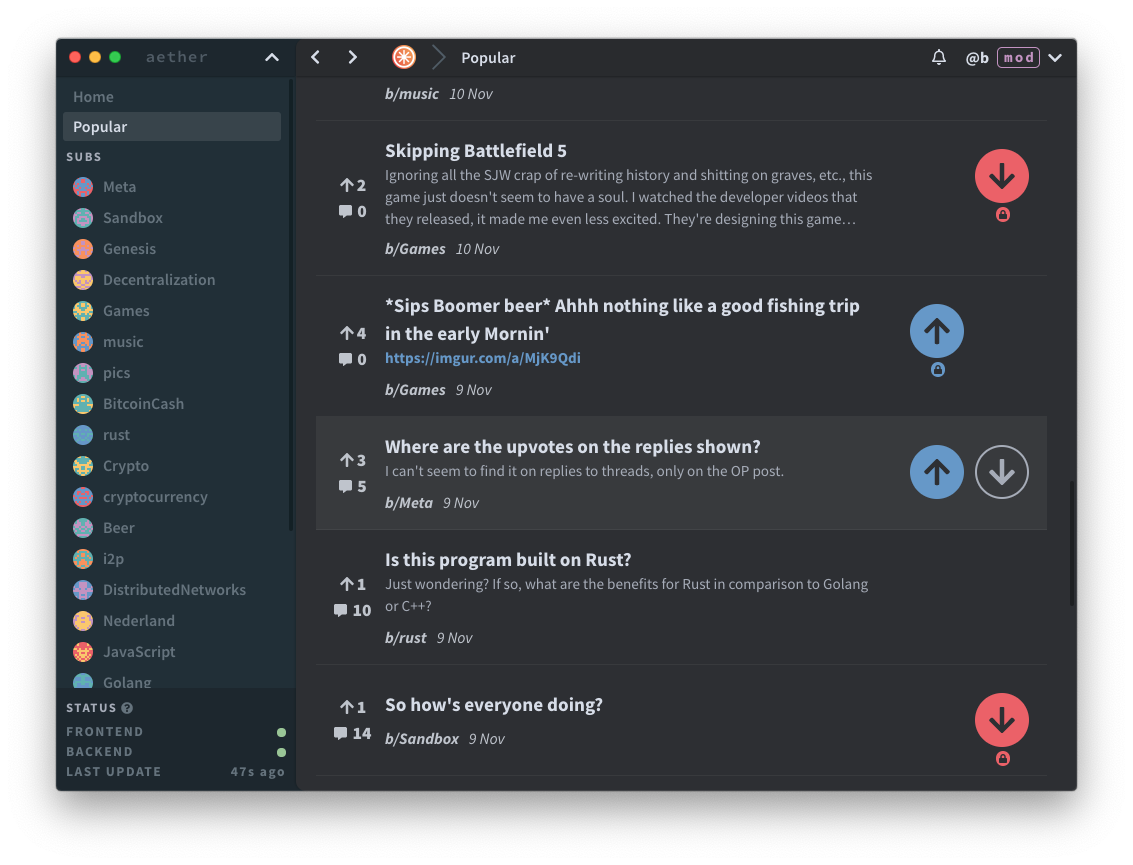

You might have seen these little locks that appear when you change your vote direction. They look like this:

You might have wondered why that has to be this way, after all, other platforms don’t have this.

The short answer

Aether relies on statistics to compact thousands of votes into manageable, but still double-count-proof buckets. These buckets can only receive a vote once, and they cannot remove a vote. That means if you upvote, then downvote, you’re now in both buckets, and if you change your mind a third time, it is impossible to discern you’re changing your vote from what to what.

The long answer

Aether faces a couple problems when compiling a flat source data set into a content graph. One of the more interesting problems is that it needs to count a lot of votes for a lot of things. If counted normally, and added to the content graph as their individual entities, these votes would take an outrageous amount of memory while serving no other purpose than just being a +1 or -1 on a post.

Consider that there can be thousands of upvotes on a post, and there can be hundreds or thousands of posts in a thread! That is a lot of nodes in a graph, and votes are as low-information-density as it gets.

If you have a thread with 100 posts, each of which, on average, getting 50 votes to either direction, you will end up with a 5000 node graph for that thread.

On the other side, if you have a thread with 100 posts, each of which has votes somehow compacted into a single entity, then you end up with a 100 node graph, which is much more manageable, and without any user-visible information loss.

Let’s think about how we can compact this information into a small bucket.

Naive case

We might start with a list of fingerprints of votes, which would give us a way to make sure that the vote is never counted twice. Whenever we want to add a new vote to the count, we check the list, and if not in the list, add it to the list and increment +1 or -1 based on the vote direction. Nice, right?

Well, here’s one issue. We not only want to make sure that a vote is counted only once, we also want to make sure that a user can only vote once on a post. As it stands, if the user creates a new vote entity, then that new vote would not be in our list, and a second vote from the same person would get added in just fine. Oops.

Here’s one more issue, and this one is more practical. When you have a thousand votes, adding the 1001st vote gets really slow, because every insertion has to check the other 1000 votes. Not good, considering we have to do this for basically every post we have, and we have a lot of posts.

But let’s ignore that practical concern for a little bit. We have an issue here - our list doesn’t include the owner keys, so owners can spam this list with abandon. Not cool! Let’s add the owner keys to the list, so that we can check for that too. So, now we’re at the point where we’re first checking that we haven’t counted the the same vote before, then we’re checking the user keys list, so as to make sure the user has not submitted another vote prior to this one. This works, but again, we’re getting even slower here. But it works! Kind of.

We have a user: Bob the Indecisive. He has decided that cats aren’t cool any more and he wants to change his vote to a downvote. So… how does that work?

As of now, he’ll change his vote by minting change on his vote object, but … the fingerprint is still the same, so is his owner key. So his updated vote won’t ever count. Ouch. We need to do something about that.

We add two timestamps into our list, the creation timestamp, and the last update timestamp. These are cool, because they allow us to determine whether a new, upcoming vote is an update to a vote that is already on the list, so that we can update the list accordingly. If creation timestamp is the same but the last update is later than what we have, we know that the vote has now changed.

The problem, you see, is that not only we’re now slow as molasses where every vote addition is costing us four full table scans, they’re also of increasing cost. But not only that, funnily enough — those four things are effectively what a vote object is, so we’re actually back to square one!

It’d save a lot of words if we just sucked it up and saved the whole vote object as part of the graph. We’d still have to sum them up and save them somewhere, but when the objects themselves are available, it gets a lot easier to disambiguate what the count should be.

There is a much better solution to this, though.

Bloom filters

Lies, damned lies, and statistics.

— Benjamin Disraeli

Bloom filters are like statistical parlour trick, but way more useful. You can think of bloom filters as magic boxes that can tell you whether the thing you have at hand was ever put into that magic box before. You can’t ever remove something from the box though. They’re cute black holes that, improbably enough, respond to questions if you ask them nicely.

Wikipedia has a great introduction to bloom filters.

So what’s happening here? We have two magic boxes, one for upvotes, and one for downvotes. We also have two abacuses beside them, so we count +1 every time we feed our boxes.

Whenever we have a candidate vote, what we do is this. We look at the vote’s owner key, which is Bob. We check both boxes. If both boxes return us negatives, then we know that Bob has never voted on this before. We place the vote into the appropriate box, increment the respective abacus, and merrily move along.

A couple days later, we get another vote from Bob. What could it be? Is Bob trying to fraud us by voting twice, or did he just change his mind? Let’s find out.

We get Bob’s new vote, and read Bob’s user key from that vote. We put the user key into both boxes. Nice - the upvotes box starts to shine, a genie appears, and says that Bob’s user key has been in that box before. The other box, the downvotes, stays dark — no matches there.

Now, what do we have here? We have a vote, which we can see from the vote itself, is an upvote. But we also got a match on the upvotes box… Uh-oh. This means either Bob has fraudulently issued a second upvote for the same post, or much more likely, that this vote has been, for one way or another, retransmitted to us accidentally. 1 So we discard that vote.

Now, in an alternate universe, we get the same vote, but it’s actually a downvote. In the same way, the upvote box lights up. That’s fine though — that means Bob has upvoted this before, and the new, coming vote is a downvote, so this is just him changing his mind. We decrement one from the upvotes abacus, and increment one in the downvote one. We just managed to register Bob’s flip-flop! Super cool. And we did this with bloom filters, which are much, much faster than scanning for vote and/or user fingerprints, creation and last update timestamps. So useful. They’re also way more space efficient than trying to store all the votes by themselves.

But here’s the catch (or trade-off, if you will). Bob changed his mind once, so we now have Bob’s key on both boxes. That means, whenever a new vote comes from Bob, we can’t actually know if it’s a retransmit, thus a duplicate vote, or Bob changed his mind yet again. Both boxes will light up, so we won’t be able to know which one to decrement, and which one to increment.

So we are forced to discard it, regardless of whether it’s a legitimate change of mind or a retransmit.

That is why Aether allows you to change your vote only once.

1 Aether is designed in such a way that this retransmit surviving in the processing path up to this bloom check is impossible, barring any bugs in the code. But let’s go with this for the sake of the story.

End note: Let a thousand flowers bloom

There are even cooler tricks in Aether with bloom filters — the method it counts populations of communities works in a similar way, too. Those populations are based on time, which means we need to be able to drop users from those bloom filters over time as they become inactive.

But did we just not say removing things was impossible just a minute ago? Yup, but Aether comes with a rolling bloom implementation that can actually do time-queryable bloom filters. 🙂1

But that’s another FAQ item for another day.

1 Keeping an accurate count of the population of a board is important, because our always-ongoing mod elections need a % of the total population to have voted for them to be counted valid, so the total population should be accurate as possible. Not only people can expire out from citizenship of a community by not posting for 6 months, and their votes with them, their votes in the elections can expire in 6 months even if they remain active, so as not to build up a permanent, immovable mound of votes that are impossible to move for the community’s newer citizens.

Resources

Bloom Filter Calculator allows you to calculate the size of the bloom filters you need for a given false positive rate and a given expected number of items in the filter.